It may be Florida, but weather has put boatbuilding in low gear, if not neutral. Nevertheless, since my past post I have gotten a few things done.

Working indoors, I put the last coat of epoxy on the centerboard. In another day or two I can wash off the epoxy blush and paint it. I'll put antifouling bottom paint on the bottom 6" and the dark shade of interior green on the rest. Also indoors, I filled and sanded all the screw holes in the rudder. It is ready for fabric coating.

Friday was the only recent day warm enough for epoxy outside. I went around the boat and marked every screw hole, nail hole, ding and crack, and followed up with microballoon filler. Yesterday, Saturday, I sanded all those spots. Quality control inspection found about a dozen spots which need redoing, and an equal number which were missed. We are in an unusual cold snap for this time of year, and it may be late next week before we see 60 degrees again. I can do some detail work indoors, but painting the inside of the hull will have to wait.

The main thing I have been doing is reading about sharpie designs and construction techniques.

Through the generosity of Capt. James Watson, the technical guru at Gougeon Brothers, I obtained copies of a series of articles Howard I. Chapelle wrote in 1956 titled

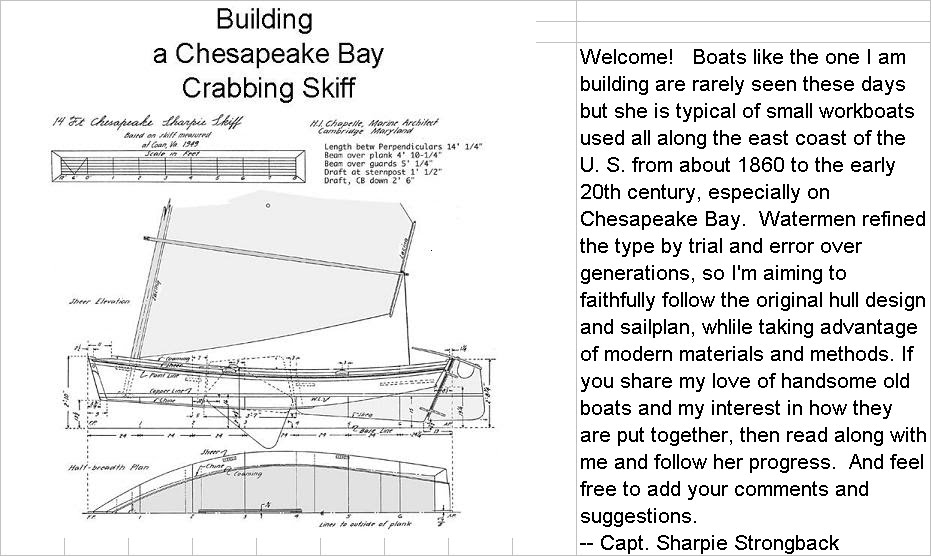

The American Sharpie Yacht. Chapelle promotes the sharpie as the ideal type for amateur boatbuilders who want the cheapest, easiest-to-build, proven type of boat practical for family sailing and cruising. He makes the case convincingly, and illustrates it with many of his own designs, adapted from old boats and traditional types. I thought the sharpie skiff I'm building was included in the articles. It isn't, but the articles make for great reading: Chapelle was both knowledgeable and opinionated. Some of his ideas are contrary to conventional wisdom, both then and especially now. I'll quote some of his remarks as space permits.

If there is one iconic sharpie in history, it was the 29' double-ender

Egret, built in New York to the design of Commodore Ralph Munroe in Coconut Grove, Florida in 1886, and used by him for many years along the coast between Miami and Palm Beach in they years before there was any road or railroad connecting them. Chapelle knew Munroe well, and made several designs based on

Egret's surviving half model. Three of those versions are illustrated in the

American Sharpie Yacht articles. Capt. James Watson built a beautiful

Egret type from one of those plans last year, and the boat is described in the Spring, 2010 issue of the online publication

Epoxyworks. Munroe was influential in spreading the popularity of sharpies throughout Florida, especially in the Keys and the Gulf coast.

In the summers of my college years I taught sailing at Coconut Grove. Each day I would lead a fleet of fledgling Optimist Pram sailers through the anchorage to the open water offshore from the Barnacle, Commodore Munroe's family home. It's now a state park, but the Commodore's son Wirth Munroe, a prolific and successful boat designer himself, lived there then. I met Wirth Munroe several times, but didn't know anything of the family's history until years later. There was a big old-fashioned catboat moored at the house, but no sharpies. Still, my new boat can claim a connection, through only a couple degrees of separation, to boats of its type in Florida waters going back over a hundred years.

Despite Chapelle's evangelism in the 1950's, there are no sharpies being built professionally now. The reason is not any fault in the design type, but material obsolescence. Sharpies have hard chines and straight sides and bottom in section. Just about all manufactured small boats are now fiberglass of course, a material which is strong on compound curved surfaces, but weaker at corners and flat surfaces. Sharpies need to be built of wood, so there will never be many of them. I just hope my boat lives up to its heritage. I can hardly wait to find out.